|

The Marquess of Ripon Table of Contents

IntroductionUndoubtedly the most celebrated member of the Lodge of Truth in bygone times was George Frederick Samuel Robinson, the Marquess of Ripon. He joined the Lodge in 1853 when he had been elected MP for Hudderfield. Ripon went on to have a distinguished career in politics, becoming Lord President of Council and Viceroy for India, whilst masonically he went on to be the Grand Master. It is extremely rare, if not unique, for a Mason who joined a Lodge outside London to go on to become Grand Master. Usually Grand Masters are connected to the Royal Family and join a London Lodge. The Lodge of Connaught & Truth is therefore most proud to count such a distinguished Brother amongst its Past Masters. The paper is divided into three sections. The first section gives a brief description of the Marquess of Ripon’s family background, the second is concerned with his political career and his contribution in shaping the world as we know it today, and last but by no means least, his Masonic career.

AcknowledgmentsThe author would like to thank Tony Denholme of the University of Tasmania, author of Ripon’s political biography, whose knowledge and understanding of the the Marquess of Ripon acted as a guide and catalyst to this work.

Lord Ripon's Family HistoryThe Robinson family can be traced back to the early sixteenth century when the fortunes of the Robinson family were established by William Robinson of York who was born in 1522. He made his money by trading with the German ports as the Hanseatic League declined, and was rewarded for his efforts by becoming Lord Mayor of York in 1581 and subsequently its member of parliament. Like most successful merchants in Tudor times he bought land and when he died Staxby and Baldersby in Yorkshire and Wotton in Lincolnshire were part of his legacy. The family survived the Civil War though Royalist in sympathy, and William Robinson’s grandson accepted a baronetcy at the Restoration and in the 1660s served as a member of the restoration Parliament. When he died in 1689 the estates passed to his nephew William who also received a baronetcy for supporting the new King. He continued the family’s connection with York and was its M.P. from 1697 to 1722. William’s grandson Thomas, elevated the Robinson’s further when he was rewarded with the Barony of Grantham in 1761 for political and diplomatic services to the Hanoverians. He married a great-great-grand-daughter of Oliver Cromwell, Frances Worsley. His son Thomas, the Second Baron Grantham, further added to the increasing wealth of the family by pursuing an undistinguished diplomatic career as Ambassador to Spain. In 1780 at the age of forty-two Lord Grantham married Mary Gemima Grey Yorke, daughter of the second Earl of Hardwicke. They proved to be a devoted couple during their short marriage, and provided a loving home environment for the two sons who survived infancy. The elder, Thomas Phillip was born in 1781 and he inherited the title and the estates when Grantham died in 1786. Additional legacies, among them the de Grey earldom in 1833, and the Ripon estates of Elizabeth Lawrence of Studley Royal made him one of the wealthiest landowners in England in the mid 1840s. As Earl de Grey he served Peel as First Lord of the Admiralty in 1834-35 and as Viceroy of Ireland in 1841-44. But it was the Earl de Grey’s younger brother Frederick John who brought the greatest distinction to the Robinson family by becoming Prime Minister, albeit for a short time, in the autumn and winter of 1827-28.

As we move on to Ripon’s political career it is important to establish the historical context. The period that Ripon entered politics, the 1850s, has a reputation for stability which was by no means apparent at the time. 1848 was the year of revolutions in Europe. Louis Philippe, the King of France was overthrown; there was revolution in Vienna and four days later in Milan. A month later a Chartist procession in London was called off as troops were mobilised. The British government of the time feared revolution may also break out. As Kitson-Clark says:-

The aristocracy still held the controlling strings in both national and local politics and public life at its best was characterised by privilege and influence acting according to the principle of noblesse oblige and at its worst by jobbery and open corruption. With such a father and uncle, however, it is not surprising that the young Ripon aspired to a political career himself. His uncle de Grey had the patronage of a number of parliamentary seats, notably Ripon, and it was perhaps, in preparation for such a career that his father arranged for him to go on a diplomatic mission to Brussels in 1849. Perhaps also his father hoped that contact with Europe in turmoil would dissuade his son from extreme radical views he had come to hold. In the company of his cousin he visited Switzerland, Italy and France. It was Paris that really inspired Ripon. On his return from Europe, Ripon associated himself with the Christian Socialists. However for over a year, Ripon does not seem to have taken a very active part in the affairs of the Christian-Socialists, largely out of deference to his father who was scandalised by his sons views and revolutionary associates. Until 1851-52 Ripon’s radical sympathies though real enough, were still largely academic and philanthropic. However, within a few months of his wedding he was drawn out of his ivory tower into the thick of an industrial dispute; the ‘lock-out’ of the engineers in the winter of 1851-52. At this point the Christian-Socialists were thrown into national prominence by their appearances on worker’s platforms, their letters to newspapers, and by their public lectures. After the final collapse of the engineers in April 1852 Ripon turned his attention to politics. The events and dangers of 1848 were still fresh in the minds of politicians and people alike, and Ripon with his working class contacts was more alive to the fact than most. According to Ripon’s political creed English life should become more democratic in the light of aristocratic failure: it is important to appreciate that in the 1850s only land owners and the middle class were allowed to vote. As Ripon saw it only administrative and parliamentary reform and ultimately the secret ballot could weaken the aristocratic stranglehold. Ripon’s parliamentary career in the 1850s assisted in the loosening of this aristocratic grip. He took with him into politics another of his radical interests: education. The 1840s saw a growing demand for an extension of elementary education. It is also interesting that W.E. Forster, the Bradford Quaker industrialist, was a friend of the Christian-Socialists. Forster and Ripon were to form a friendship at this time which bore fruit in the Education Act. This piece of legislation is considered so important that Bradford erected a statue in Forster’s name and named a square in the city centre after him. In view of his persistently held advanced opinions, his uncle de Grey would neither sponsor Ripon, nor provide him with a family pocket borough, the usual method by which young aristocrats were launched into politics. Left to his own resources Ripon’s choice of a constituency descended upon Hull, a tough sea-faring borough with a bad electoral reputation for dishonest practices. Ripon took great pride on his clean electioneering behaviour, ironically however, shortly after being elected a member of parliament for Hull he was unseated after accusations of bribery. To such a man of honour and integrity this smirch must have been extremely hurtful. However, it did not put him off and he was determined to get back into the Houses of Parliament in order to do which he stood for election at Huddersfield. As Denholme says:-

On Saturday 17 April, Ripon addressed a crowd, estimated at 10,000, as part of his electioneering campaign, four days later he was elected for Huddersfield, receiving 675 votes to Joseph Starkey’s 593. It was not as apathetic a turn out as the figures suggest but it does accentuate the differences between our two times, indeed Ripon witnessed at first hand the basis of the changing democracy in nineteenth century Britain.

Career at the War Office Between 1853 and 1859 Ripon had established himself as an expert on military matters, with definite views on the necessity for the abolition of purchase and for improving the efficiency of the service. It was this reputation that led to him joining Palmeston’s administration in 1859 as Under Secretary of State for War under Herbert. Ripon like many other radicals welcomed the Crimean War (1853-6) as a war against the tyranny Czardom, but he also relished the opportunities presented by the mismanagement to press home the argument he had been making in public for over two years.

His success as Secretary of State established his administrative reputation and made it certain that he would be given further office. On the death of Sir George Lewis, who had succeeded Herbert, Ripon got his long-looked for promotion and entered the cabinet as Secretary for War in 1861. His promotion and term of office coincided with the start of American Civil War of 1861-5. On matters of sanitary reform, Ripon worked closely with Florence Nightingale and the fruits of their labour were a changed attitude on the part of the army towards hygiene and the status and role of medical officers. Lord President of Council By the time Gladstone returned to power in 1868 Ripon had established a reputation as an enlightened and efficient administrator. Though Ripon would have preferred to return to the War Office Gladstone offered him the Lord Presidency of the Council. Ripon was not unhappy with the position for it gave him ministerial responsibility for educational questions which were at that moment were "of particular urgency and importance". Ripon’s achievement was sweetened further by the success of most of the other Goderichites. Bruce, though he had lost his seat at Merthyr, became Home Secretary and a new seat at Renfrew was soon found for him. Forster, after some hesitation accepted the vice-presidency of the Council under Ripon. The unique social and romantic radicalism of the Goderichites had at last found a home under the broad umbrella and moral imperatives of the Liberal Party. Much of what Ripon had campaigned for in the 1850s came to fruition in the late 1860s and early 1870s. In particular two pieces of legislation were introduced which he had supported since his early parliamentary days became law; the secret ballot and the education act. Ripon had been an advocate of the secret ballot from his Christian-Socialist days, and it must have given him great pleasure to introduce this measure to the House of Lords as the Electoral (Parliamentary and Municipal) Bill on its second reading on 10 August, 1871. In addition Ripon had departmental responsibility for introducing the most far reaching reform of elementary education in the nineteenth century of which he was later to say "one of the matters of which in a long public career I am most proud". In doing so he realised another of his earliest dreams, that of bringing elementary education to the masses. At his side was his long time friend, confidant and sympathiser in the education cause, W.E. Forster. Throughout his life Ripon held high hopes of the spread of education to the working classes, not only because he believed it absolutely necessary for emerging democratic society, the commonly held view of "educating our masters", but more because it was an instrument for elevating the masses. During Ripon’s tenure as Lord President and W.E. Forster tenure as Vice-President the two men were able to effect a number of substantial educational reforms that virtually revolutionised the attitude of British governments to education, and which established models and patterns for future state intervention. By bringing about the active participation and complete involvement of the state in the educational system the two men gave it a social responsibility that it could not discard. Another one of Ripon’s abiding interests in promoting education was the Mechanics Institutes, especially as they were the only means of working class education for adults outside London. Ripon’s roots and his political interests lay in the North of England and not surprisingly therefore most of his work for the Institutes were confined to Yorkshire, and to Huddersfield in particular. Alabama Treaty The highlight of Ripon’s tenure in office in Gladstone’s administration was his work on the joint Anglo-American High Commission of 1871 which settled serious outstanding points of difference between Britain and the U.S.A., indeed so serious was the state of Anglo-America relations at the time that war seemed inevitable. The failure of the British to understand the deep sense of grievance felt by the Americans over the fitting out of the Alabama and other Confederate ships in British ports at the time of the Civil War largely accounts for the deterioration of relations in the late 1860s. But the crisis reached its flashpoint over the Alabama claims. These differences concerned the building of ships for the Confederate Navy in British shipyards and subsequent hospitality to such ships in British Empire ports. These activities were made possible, as Americans saw it, by the inadequacy of the British neutrality laws and their lax enforcement. The British statute on neutral conduct, the foreign enlistment act of 1819, forbade the equipping, furnishing, fitting out, or arming within British jurisdiction of vessels for the purpose of attacking the commerce of friendly powers, or the augmentation of "the warlike force" of such vessels, but did not prohibit the building of such vessels. Taking advantage of this loophole in the law, Captain James D. Bulloch, the Confederate agent charged with such business, arranged with English shipbuilding firms for the construction of the ships, which became famous as the Confederate cruisers Florida and Alabama. In each case the ship was built but not "equipped, fitted out, or armed" in a British shipyard. Each put to sea without equipment and in a remote unpoliced sanctuary - the Florida in the Bahamas, the Alabama in the Azores - met another steamer bringing her armament, officers, and crew.

The United States held also that Great Britain had violated the principles of neutrality in permitting confederate cruisers to augment their strength in ports of the British Empire. The Shenandoah, for example, had put in at Melbourne, Australia, where in spite of protests from the United States consul, she was allowed to make repairs, take on a supply of coal, and recruit additions to her crew. In addition to the actual destruction wrought by the Alabama, Florida, Shenandoah, and less celebrated raiders, their depredations had caused a skyrocketing of insurance rates, kept ships idle in port, and driven many northern ship-owners to sell their vessels or transfer them to foreign registry. For all these losses British negligence or partiality was held responsible. With Canada defenceless, it was possible that the whole of North America would be brought into the vigorously expansive post-war United States. Britain, with its army still largely unreformed, was militarily paralysed and yet faced the possibility of war on two fronts. Into the midst of this potentially war-like threat Ripon was dispatched as Chairman of the Joint Commission. Ripon’s approach of conciliation and compromise won widespread praise and he succeeded in diffusing the tension between the United States. Tanterden, who was the secretary to the British commissioners commented on:-

For Britain’s failure to exercise "due diligence" over the Alabama, the Florida and the Shenandoah she was asked to pay £3 million. In the long run the Washington Treaty which settled the Alabama claims as they were commonly referred to was a landmark in the history of international law and lead to much improved relations after the dark years of the 1860s. Furthermore, it completed the withdrawal of the British from North America without bloodshed, yet still left Canada intact. This altered Britain’s perspective in the region which according to Stacey, Britain had:-

For his role in the successful negotiations Ripon was given a marquessate and thus in 1871 he became the Marquess of Ripon. Conversion to Catholicism In August 1873 Ripon resigned from Gladstone’s government, chiefly he was gloomy about the future direction of the Party. By 1873 the great reform ministry was a spent force. The heady achievements of the early years had given way to a disillusionment among the rank and file, and a growing desire by a number of cabinet ministers to be free. However Ripon’s resignation was probably due to "spiritual unrest". His mother, to whom he was devoted and who had been his only intellectual and religious guide until late adolescence, died in 1867. F.D. Maurice, his political mentor of the 1850s, died in 1872, close relatives had been massacred by Greek brigands in 1870, and his son had been close to death in 1873. In September 1874 some rather surprising news was revealed which, one hopes, by today’s more enlightened times would hardly raise an eyebrow. Apparently Lord Ripon had converted to Catholicism. Unfortunately Ripon’s conversion coincided with one of two outbreaks of anti-Catholic sentiment in England during Victoria’s reign. The first was in 1850 after the Catholic Church had been permitted to re-establish its hierarchy in Britain, and the other followed the Vatican Council of 1870, and in particular the assertion of Papal Infallibility. His reception into the Catholic Church took London society and even his closest friends by surprise:-

Ripon had been an active Freemason for over twenty years and had become Grand Master in 1870, but he attended his first mass at St. George’s Cathedral, Southwark in April 1870, the Sunday following the assassination of his father-in-law Frederick Vyner. As he grappled with the full implications of a possible conversion to Catholicism it is not difficult to imagine the confusion in his mind as long cherished ideas came under review.

However, it is generally agreed that the foreign and imperial policies of Disraeli’s government were the major reason for Ripon’s active return to political life. Both Rossi and Wolf stress the outbreak of war with Afghanistan in the summer of 1878 as a crucial date. Ripon was vexed that the deliberate policy of forty years should be reversed and that the country had become involved in a war without Parliament ever having had the slightest opportunity of expressing its opinion on the subject. He soon became one of the leading spokesmen on Indian affairs for the opposition, and along with Lord Northbrook (an ex-viceroy) and Lord Halifax he became one "of a triumvirate which substantially shaped opposition policy regarding India and Afghanistan". The Viceroy of India

Lord Privvy Seal

When Viscount Goderich was admitted into the Lodge of Truth in 1853 he joined a Lodge which was markedly different from the one today. For a start the Lodge of Truth then met in a room which had been specially built at the Rose and Crown, an important posting and commercial house at the lower end of Kirkgate. The Rose and Crown was opposite what is now the Huddersfield Hotel. The Rose and Crown was demolished some time ago and gave way to the Palace Theatre and now serves as a bingo hall. The Lodge of Truth was only eight years old when Ripon joined in 1853, however it had a membership of sixty-three. The membership had seen a massive boost from a humble eighteen in 1851 to fifty-two "in the remarkable year of 1852" (Simpson 1945, pp. 27-33). In 1852 Brother John Sykes, a joining member from the Lodge of Harmony, was in the chair. During his year there were thirty-three initiations, twenty-nine passings and twenty-three raisings! Even the lodge number was different in those days. Ripon joined The Lodge of Truth No. 763 of the United Grand Lodge of England: the lodge numbers were reallocated in 1863. From the minutes of one-hundred and fifty years ago it becomes obvious, at least in the first few years, that attendance was not as regular as it is nowadays. Unfortunately this situation is exacerbated by the fact that the names of Brethren attending the Lodge are not recorded in the minutes. The Initiation of Lord Ripon The story of Ripon’s Masonic career starts on 27th April 1853 when, he wrote a letter to Brother John Sykes, the same John Sykes who had initiated thirty-three candidates the previous year. I doubt Ripon’s letter to Brother Sykes still exists, which is a shame because it may have contained some valuable information. However, on the following day of 28th April 1853 Brother Sykes wrote a letter to the then Worshipful Master, Brother Thomas Robinson nominating Ripon as a candidate for Freemasonry. In this letter, a copy of which is given in Appendix A of this paper Brother Sykes states:-

This letter has nine other names of members of the Lodge of Truth on the bottom, in addition to that of Brother Sykes.

Ripon was indeed balloted for on 6th May 1853 at the next regular Lodge. At the tender age of twenty-five he was initiated as the 91st member of the Lodge of Truth on Tuesday 17th May 1853 at an Emergency Lodge. The reason an Emergency Lodge was called, something far more common in those days than today, was that Ripon was unable to attend the regular Lodge meeting owing to parliamentary duties. According to Simpson (1945, pp. 35-36) the honour of initiating Ripon went to Brother Hardy, a Past Master of Fortitude and Old Cumberland Lodge No. 12. Brother Hardy had become a joining member of Harmony in 1852, thence a joining member of the Lodge of Truth only three months before Ripon was initiated, in February 1853. Hardy was the Head of Huddersfield College and, according to Simpson was a "man of literary attainment and apparently well-skilled in the noble order". I think Simpson may have jumped to an incorrect conclusion. In the very short minutes of Ripon’s initiation it merely states that "Brother Past Master Hardy very pleasingly illustrated the First Tracing Board". These minutes are duplicated in Appendix B. There is no mention of who was in office that night and, from what I can see, no evidence to suggest anything but that the officers of the year took part in the ceremony. Ripon's Affinity for Freemasonry

Freemasonry in Ripon’s time was seen as a somewhat radical organisation which held progressive ideas on how society should be organised: an essentially democratic view which today one takes for granted. In particular Freemasonry’s egalitarian principles were at odds with the ruling class at that time. To make a comparison of a famous predecessor, Robert Burns died thirty-one years before Ripon was born. According to a posting on the internet, the National Museums of Scotland states that "Burns was a man of strong and passionately held views on the issues of his day. His commitment to Freemasonry at that time marked him as a man of liberal and egalitarian views". Being the voracious reader he was, Ripon may well have read one of the many exposés of Freemasonry, the first of which was by Samuel Prichard and appeared as far back as 1730 in the Daily Journal. If indeed if he did read the exposés, he may well have come across such sentiments as are conveyed in the presentation of the Second Degree Working Tools:-

As a radical and essentially egalitarian person who was interested in introducing democracy to the masses he would have found Freemasonry in tune with his own philosophy. It is probable then that Ripon would have agreed with such sentiments:-

Ripon’s deep religious and political convictions were the cornerstones of his purpose in life, he found Freemasonry to be entirely empathetic with his persuasion:-

Having proposed some reasons why Ripon might wish to associate with Freemasonry, one has to ask why Ripon chose to join to Lodge of Truth. Ripon wrote his letter of application to Brother Sykes on 27th April from his London residence of 5 Whitehall Yard; this was merely four days after being elected to parliament as the M.P. for Huddersfield. It may have been an "extension of his lively interest in borough affairs" (as Denhome put it) that Ripon chose to join a Lodge in his constituency, joining a fraternity the philosophies of which he so readily identified. Here was an opportunity for him to meet and associate with the influential townsfolk, however, one thing is for sure it was not one a decision he took lightly. If one reads between the lines of the letter from Brother Sykes reproduced in Appendix A it does not appear that his proposer, Brother Sykes, actually knew Ripon. For example, Sykes does not propose and second Ripon in the normal manner, instead he nominates him. Additionally Sykes adds seven other members names to his motion, as if he were submitting a petition. These extraordinary lengths would not have been required had the normal rules of the Book of Constitutions applied and the request to join the Lodge of Truth may well have been have a ‘bolt out of the blue’. There may be a number of possible connections and this is, I would emphasise speculation. In the previous year on 14th April 1852 the Provincial Grand Master the Right Honourable the Earl of Mexborough attended a Provincial Banquet which was hosted by the Lodge of Truth. 1852, you may remember, is the year that our old friend Brother Sykes was in the chair and apparently initiating, passing and raising the whole of the borough Huddersfield.In the circles that Ripon moved in he probably knew the Earl of Mexborough and that was the Provincial Grand Master. It may have been on Mexborough’s recommendation that Ripon joined the ‘up and coming’ Lodge of Truth. We also have to look at the application for membership from the Lodge’s point of view. Whilst he may well have been the son of a nobleman he was also a young man, as we have seen of "persistently held advanced opinions" whose uncle would not sponsor for a seat in the Houses of Parliament. At this time Brother Sykes could not have known whether Ripon would turn out to be a loose canon or a future Grand Master and we have to acknowledge Brother Sykes’s sound judgment in this matter. Membership of the Lodge of Truth Ripon was passed on the 12th October 1853 and raised one month later on 25th November, both at Lodges of Emergency (probably owing to his parliamentary duties). Hardy gave the second degree tracing board but unfortunately the minutes do not reveal who took part in his Lordship’s raising. Two years later, in 1855 Ripon was installed into the chair of King Solomon as the tenth Worshipful Master. This means it took him just over two years to get to the chair, having spent the obligatory year as a Warden. Although his officers were invested in December, Ripon was not installed until June of the following year. Simpson states:-

From Denholme we know Ripon had actually been holidaying in Pau in November 1854 and was also in the Pyrenees in March 1855 (Denholme 1982, p.50 and p.87). It appears Ripon may have been on an extended holiday (!) The year that Ripon was in the chair was a very significant one for the Lodge of Truth for it was during his term of office as Worshipful Master that the Lodge moved to Fitzwilliam Street in Huddersfield. The removal of the Lodge had first been suggested in open Lodge on the 25th November, 1853 (the same night as Ripon’s raising), although no doubt many informal discussions will have preceded. The foundation stone to Fitzwilliam Street was laid on Wednesday 27th December 1854 on the Festival of St. John. by Brother George Wright. He was Ripon’s predecessor in the chair and would have probably been deputising for him in Ripon’s absence. Friday 5th October 1855 was the first regular Lodge meeting held at Fitzwilliam Street and the Deputy Provincial Grand Master "allowed a dispensation of [Ripon’s] presence when the motion of removal is made" (Simpson 1945, p.38). Coincidentally, this makes Fitzwilliam Street one of the oldest purpose-built Masonic temples which is still in active use in the Province of Yorkshire West Riding. Ripon was away in Scotland at the time of the first meeting, however the Worshipful Master sent a cheque towards the building of the new hall for £20. In today’s money this donation would be worth about £1,000. In the following year of 1856 and having completed his year in the chair Ripon was given Grand Lodge honours and became the Senior Grand Warden. The following year Ripon became a joining member of the Wakefield Lodge No 495. This decision coincided with two events, first he was returned as Member of Parliament forYorkshire West Riding and a local land owner and colliery owner called Col J C D Charlesworth had joined Wakefield Lodge two months earlier. Ripon's Rise to the Provincial Grand Master In 1861 the Earl of Mexborough died and was succeeded to the high office of Provincial Grand Master by Ripon who was now thirty-four years old. Ripon’s appointment to Provincial Grand Master proved to be most popular in the Province:-

Strenuous efforts were made to host the installation in Huddersfield and the three Huddersfield Lodges at that time, Harmony Huddersfield and Truth combined to lobby Province. But it was not to be. The Leeds Committee sent representatives to The Lodge of Truth to say that Leeds possessed superior accommodation in the form of Victoria Hall, and that if the Huddersfield Lodges would withdraw its claim they would allow His Lordship to be installed in Leeds under the Banner of The Lodge of Truth; the Officers of the Lodge to open and close the Lodge. This was indeed done on the 22nd May, 1861. However, owing to a regrettable oversight the brethren of the Lodge of Truth were not allocated Banquet Tickets. Ripon was most apologetic about the incident and that:-

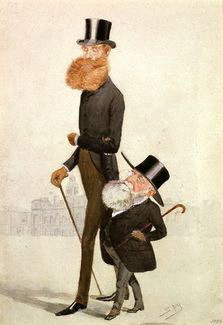

His appointment as Provincial Grand Master seems to have enlivened Ripon, and in addition to the Lodge he had joined at Lincoln two years previous (Witham Lodge No. 297 in Lincoln) he joined two other London Lodges. On 11th June 1861 he joined the Lodge of Friendship No. 6 (a Red Apron or Grand Stewards’ Lodge) and on 2nd July he joined Royal Alpha Lodge No. 16. Royal Alpha is the Grand Master’s personal lodge and Ripon made it a point to be at each installation. He was its Worshipful Master three times, namely the year after he joined in 1862, then again in 1870 and 1874. As we have seen from the extract from The Freemason the Provincial Grand Master Ripon was highly involved in the affairs of the Province. On 19th April, 1865 at a Provincial Grand Lodge held in Huddersfield he laid the foundation stone for The Mechanics Institute at Lockwood. As we have seen Ripon had an abiding interest in education and Mechanics Institutes were the only place adults could receive education outside London and was twice chairman of the Yorkshire Union of Mechanics Institutes. Appropriately enough to this paper the Mechanics Institute in Lockwood, with its fine façade, was restored in early 1997 and has been converted into flats. A far more appropriate use than the empty shell it was when I first visited it in 1996. I think Ripon would have thoroughly approved of the University of Huddersfield a mile down the road which dwarfs this small building which was, nevertheless, a testament of the first step towards providing local adult education. Ripon's Rise to Grand Master In the same year that he become Provincial Grand Master Ripon was also appointed Deputy Grand Master by The Right Honourable the second Earl of Zetland. On 2nd March, 1870, on the retirement of Zetland, he succeeded to the Grand Mastership, and was in due course installed to the throne of King Solomon on the 14th May 1870 (Masonic Year Book 1991-92, p.814 Outstanding Masonic Events) As the magazine the Freemason stated:-

As an example of this "brilliant and fruitful" period he introduced the then Prince of Wales (afterwards King Edward VII) to Royal Alpha Lodge.

Speaking on a familiar theme in reply to an address of welcome, he said:-

He went on to say:-

In 1871 after his negotiation of the Washington Treaty he became the first Marquess of Ripon and on the 22nd January 1873 at a Provincial Grand Lodge held at Huddersfield a congratulatory address was made to Ripon on attaining his majority; he had been in masonry for twenty-one years. On 4th March 1874 Ripon was re-elected for the fifth time as Grand Master. On this occasion he gave a speech expressing his deep gratitude:-

During Ripon’s reign as Grand Master the body of the Order flourished mightily. The number of new Lodges for which Ripon was privileged to grant Warrants reached a higher proportion than it had during any previous period. In fact, the number of the Lodges warranted by Ripon was two-hundred and sixteen. Indeed during Ripon’s reign as Deputy Grand Master and Grand Master he warranted many local lodges to the Province of Yorkshire West Riding, for example Trafalgar and Scarborough in Batley; Mirfield Lodge; Saville at West Vale; Ryburn at Sowerby Bridge; Brighouse; De Warren at Halifax and last but by now means least, Thornhill at Huddersfield. A full list of Lodges he warranted is given in Appendix C. Additionally there are six Lodges that I know of that were named after Lord Ripon. The first of these were de Grey and Ripon (No. 837) which meets at Ripon in the Province of Yorkshire West Riding. The second de Grey and Ripon Lodge (No. 905) was formed in 1862 and met at the Cafe Royal, London, this Lodge handed in its warrant in the early months of 2000. A third de Grey and Ripon Lodge (No. 1161) meets in Bridge Street, Manchester in the Province of East Lancashire and was formed from its mother Lodge Caledonian No. 204 in 1867, when Ripon was Deputy Grand Master. (Unfortunately de Grey and Ripon No. 1161 handed its warrant in in October 2004 http://www.mqmagazine.co.uk/issue-11/p-24.php). Finally, there is the Marquess of Ripon Lodge (No. 1379) which meets in Darlington in the Province of Durham. The following year of 1868 Goderich Lodge (No. 1211) which now meets at Headingley in Leeds was consecrated. The name Goderich was probably chosen because there was already a Lodge named after de Grey and Ripon in the Province of Yorkshire West Riding. However, Ripon graciously consented the Lodge the privilege of using his coat of arms and crest and became the only Lodge in the country to be allowed to do this. Finally, during his reign as Grand Master the Marquess of Ripon Lodge (No. 1379) of Darlington, Province of Durham, was consecrated and is the only one to bear his marquessate title. As previously mentioned Ripon was accepted into the Catholic Church on the 8th September, 1874. Although he was well acquainted with the relations between the Craft and the Papacy, apparently he was slow to believe that the Papal Bulls which had been levelled at the Craft were still valid. However, when at the last moment the attitude of the Vatican in regard to Freemasonry was made clear to him, it was relatively much too small a matter to modify the grave decision at which he had arrived. Ripon resigned having withdrawn from the Craft on 2nd September, 1874 sacrificing his political and Masonic career for the greater universal spiritual company of the Roman Catholic Church. At this time Ripon has been in Masonry for twenty-one years, of which he had been the Provincial Grand Master for thirteen years, and the Grand Master for four years. Coincidentally, the lodge rooms on Skellgate in Ripon, still have his regalia as Provincial Grand Master on display. According to the apocryphal story, Ripon gave his regalia for the gardener to burn when he resigned from the Craft. The gardener never carried out his instructions and, thinking that it was worth something of value, kept hold of it. Eventually the regalia found its way to the local lodges. Ripon resigned from public office in 1901 at the age of 81. He spent much time in London where he was honoured by the Eighty Club at a luncheon in November of that year. On this occasion he made a speech in response to a very warm welcome by the Prime Minister, Asquith:-

The end came quite suddenly. On the morning of Friday 9 July 1909 he suffered a heart seizure and died later the same day, an hour before his son arrived. He was buried at the church of St. Mary the Virgin in the grounds of his beloved Studley Park. I will leave the final words to a quote from Denholme’s book on Ripon which neatly encapsulates the life and times of the First Marquess of Ripon:-

Books Baker, G. (1979) Private Members, Liberalism and Political Pressure : a mid-Victorian case study. University of Adelaide, PhD. 1979. Craddock, JR The Marquess of Ripon, (n.d.) an occasional paper used as a lodge lecture. The Earl of Oxford and Asquith, K.G. (1926) Fifty Years of Parliament, Cassel and Company Ltd, London. Denholm, A. (1982) Lord Ripon (1827-1909) - A Political Biography, Croom Helm, London & Canberra Lord Esher (1922) The Quarterly Review, No 471, April 1922, p.221. Kitson-Clark, G. (1962) The Making of Victorian England, London, 1962. Mathur, L.P. (1972) Lord Ripon’s Administration in India (1880-84), S. Chand & Co (Pvt) Ltd, Ram Nagar, New Delhi. Masonic Year Book 1991-92, p.814 Outstanding Masonic Events Newbould, I. (1990) Whiggery and Reform 1830-41, MacMillan, London Pratt, J.W. (1965) A History of United States Foriegn Policy, Prentice-Hall Inc., Englewood Cliffs, N.J. (Second Edition) The Quarterly Review, Vol 166, Jan-Apr. 1888, pp. 264-5. Reid, T.W. (1888) Life of the Rt Hon W.E. Forster, Adam & Dart, Bath Rossi, J.P. (n.d.) Lord Ripon’s Resumption of Political Activity Recusant History Simpson, H.L. (1945) The Lodge of Truth No.521 (1845-1945), Limited Edition. Stacey, C.P. (1955) Britain’s Withdrawal from North America 1864-1871 Canadian Historical Review, Vol. XXXVI, No.3, 1955. Thomas, G., (1969) Lord Ripon - The Father of Self-Government, Indo-British Review, Vol I, No.3. Worts, F.R. The Goderich Lodge No.1211 Leeds (1868-1943) Waite, A.E. (1970) A New Encyclopaedia of Freemasonry. Who Was Who 1897-1915 p. xxxix. Wolf, L. (1921) Life of the First Marquess of Ripon, 2 Vols. Periodicals The Freemason, 27th May, 1922 A Notable Past Grand Master, The First Marquis of Ripon. The Times Saturday 5th September, 1874, page 9. Loose Leaf Notes held at Grand Lodge Library Letter from Grand Library to Brother Heatley, 5th February 1976. A New Arrangement for the Entered Apprentices Song Internet National Museums of Scotland "An Exhibition in Celebration of the Life, Times and Legacy of Robert Burns" - taken for the internet www.nms.ac.uk/exhbition.html (21st October 1996). http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/F._J._Robinson,_1st_Earl_of_Ripon http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Robinson,_1st_Marquess_of_Ripon http://www.bl.uk/reshelp/findhelpregion/asia/india/indianindependence/indiannat/source1/index.html http://www.enotes.com/topic/George_Robinson,_1st_Marquess_of_Ripon http://www.mqmagazine.co.uk/issue-11/p-24.php Letter Proposing Viscount Goderich as a Candidate for Freemasonry

To Thos. Robinson Esqr. Worshipfull Sir and Brother, We the undersigned being Members of the Lodge of Truth No. 763, held at the Freemasons Hall, Kirkgate, Huddersfield, hereby nominate George Frederick Samuel Robinson commonly called VISCOUNT GODERICH, Member of Parliament, residing at No. 5 Whitehall Yard, London, aged 25 years, as a Candidate for Freemasonry, and we affectionately request that you will cause his Lordship’s name to be inserted in the next summons for the regular Lodge Meeting of Friday the sixth of May, and issued seven days previous to such meeting as in accordance with Constitutions Page 85 Section 2. The reason why this Emergency is urged is that his Lordship cannot leave his Parliamentary duties for a longer Period than during his next visit to Huddersfield, about this time, and having long contemplated joining our honourable fraternity, his Lordship has evinced such a strong desire to become a Member of the Lodge of Truth, as expressed in a letter from his Lordship to Br. Sykes, P.M. dated London April 27th 1853. We are Worshipl. Sir and Brother, Yours very faithfully and fraternally, John Sykes, P.M. G.T. Wright, S.W. Thos. R. Tatham, P.M. Wm. Cross Marsh, J.W. Itus Tewlis, P.P.G.S.B. and P.M. Walter Bradley, S.D. Michael Kemp, P.J.W. William Hewitt Shepherd, Secy. Thomas Abbey Bottomley, M.C. [The page is entitled The following letter was rec’d from the WM and entered accordingly and appears opposite the minutes taken on Friday May 6th, 1853] The Minutes of Viscount Goderich’s Initiation

Consecreation Dates of Local Lodges Lodges Consecrated in the Province of Yorkshire West Riding when Ripon was Deputy Grand Master (1861-1870) and Grand Master (1870-1874). (N.B. These are approximate only and some require verification with the respective Lodges).

The Marquess of Ripon’s Entry in Who Was Who Ripon, 1st Marquess of (created 1871), George Frederick Samuel Robinson, K.G., P.C., G.C.S.I., C.I.E., D.L., J.P., D.C.L. (Hon Oxford), Litt.D. (Hon. Victoria), F.R.S. ; Baronet. 1690 ; Baron Grantham, 1761; Earl de Grey, 1816 ; Viscount Goderich, 1827; Earl of Ripon, 1833 ; Lord Privvy Seal, 1905-8 ; Lord-Lieut. N.R. Yorkshire, 1873-1906 ; High Steward of Hull ; Hon. Col. 1st Batt. W. York Rifles since 1860 ; became a Roman Catholic, 1874 ; (2nd Lord Grantham concluded the preliminaries of peace with France, 1783) ; b. London, 24 Oct. 1827 ; son of 1st Earl and Sarah, only daughter of 4th Earl of Buckinghamshire ; succeeded father and uncle, 1859 ; married 1851, Henrietta Anne Thedosia, C.I. (d. 1907) daughter of Captain Henry Vyner, Gautby Hall, Lincolnshire, grand-daughter of 1st Earl de Grey ; one son. M.P. for Hull, 1852-53; for Huddersfield 1853-57 ; for Yorkshire West Riding, 1857-59 ; Under-Secretary for War, 1859-61 ; to India Office as Under-Secretary, 1861-63 ; Secretary of State for War, 1863-66 ; Secretary of State for India, 1866 ; Lord President of Council, 1868-73; Chairman of Joint Commission for drawing up Treaty of Washington, 1871 ; Grand Master of Freemasons, 1871-74 ; Gov.-Gen of India, 1880-84 ; 1st Lord of Admiralty, 1886 ; Sec for Colonies, 1892-95 ; Mayor of Ripon, 1895-96. Owns about 21,800 acres. Heir : Son, Earl de Grey, q.v. Address 9 Chelsea Embankment, S.W. ; Studley Royal, Ripon. Clubs : Brooks’s Reform, Traveller’s Athenaeum, United Service. (Died 1909). Source: Who Was Who 1897-1915 p. xxxix. n.b. This entry fails to mention the fact that Lord Ripon was the first Chancellor of the University of Leeds. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

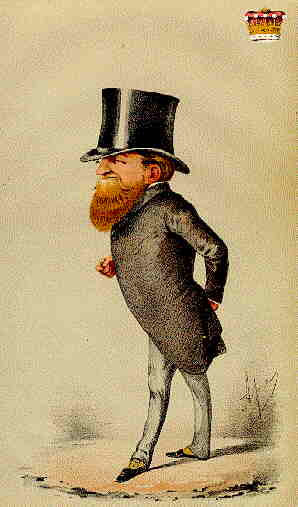

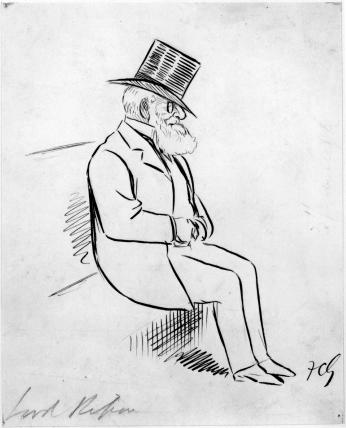

| Images of HRH Albert Edward, Prince of Wales and Marquess of Ripon as Grand Master courtesy of FreemasonCollection http://www.freemasoncollection.com for which we are most grateful. |

Frederick

John Robinson, 1st Earl of Ripon , styled

The Honourable F. J. Robinson until 1827

and known as The Viscount Goderich

between 1827 and 1833.

Frederick

John Robinson, 1st Earl of Ripon , styled

The Honourable F. J. Robinson until 1827

and known as The Viscount Goderich

between 1827 and 1833.